NEW YORK’S LONG ITALIAN SUMMER OF 1972

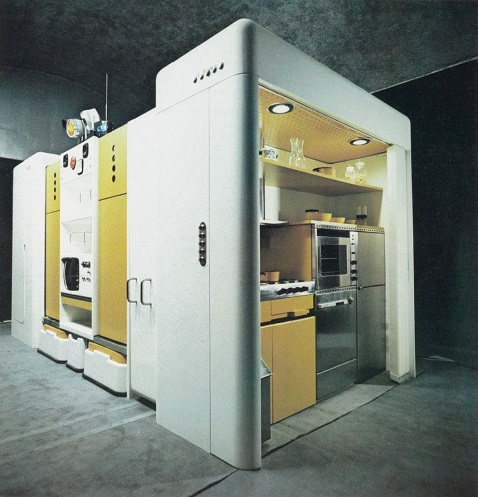

CREDIT: DIGITAL IMAGE, THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK/SCALA, FLORENCE ‘TOTAL FURNISHING UNIT’. DESIGN BY JOE COLOMBO IN COLLABORATION WITH IGNAZIA FAVATA, ARCH., 1972. ILLUSTRATION FROM ‘THE NEW DOMESTIC LANDSCAPE’ CATALOGUE OF MOMA EXHIBITION, 1972 (PHOTOGRAPHER: ALDO BALLO). THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART LIBRARY, REF. NO.: 300062429_0183

“Total Furnishing Unit: Joe Colombo’s Ingenious Compact Living Solution for the Urban Dwellers of Tomorrow a fully fitted kitchen, a bathroom, a sleeping corner and a wardrobe, all in 28 square metres.

In the history of italian Design, a turning point was marked by 1972. It was the year when, in the eyes of the word, Italy moved away from the romanticised notions of the Grand Tour and Renaissance masters clichés, and discarded the pedestrian stereotype of chequered tablecloths and hanging garlic beads, at least for the sophisticated universe of contemporary design. That year, at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, America and the world fell under the spell of a groundbreaking exhibition, as a group of Italian avant-garde designers and architects left an indelible mark and influenced global design trends forever.

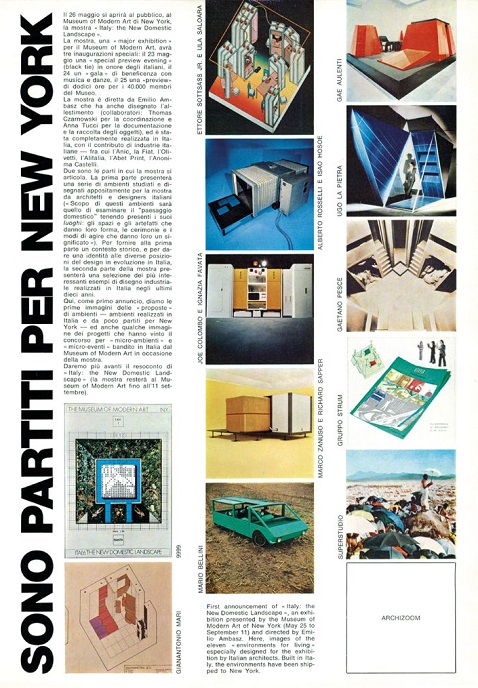

“Domus”, one of Italy’s most authoritative architecture magazines, provided comprehensive coverage of the exhibition.

“Domus”, one of Italy’s most authoritative architecture magazines, provided comprehensive coverage of the exhibition.Compared to its counterpart free-standing modelCredits: Domus 510, maggio 1972, p.21 - Archivio Domus © Editoriale Domus S.p.A.

The exhibition was called “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape”, and it was a bomb. Not only was Italian Design alive and kicking, but it was leading the pack and offering fascinating, visionary perspectives on society’s evolution in those incredibly dynamic years, on the emergence of new lifestyles and our very own and deep perception of modern living in general.

Here’s how MoMA itself presented the exhibition in the opening lines of a press announcement released on May 26, 1972, acknowledging the historic significance of the event right from the onset: “Italy: the new domestic landscape, one of the most ambitious design exhibitions ever undertaken by The Museum of Modern Art, will be on view in the galleries and garden from May 26 through September 11. […] the exhibition reports on current design developments in Italy with 180 objects for household use and 11 environments commissioned by the Museum.”

The exhibition was directed and installed by Emilio Ambasz, the Argentinean Curator of Design in the Museum’s Department of Architecture and Design.The relevance of the event, and indeed of Italy and of Italian Design on the world contemporary scene was also expressed by Ambasz: “Italy is not only the dominant product design force in the world today but also illustrates some of the concerns of all industrial societies. Italy has assumed the characteristics of a micro-model where a wide range of possibilities, limitations and critical problems of contemporary designers throughout the world are represented by diverse and sometimes opposite approaches.”

Columbus journey, reloaded

On their epic journey to New York, the eclectic band of brothers led by Ambasz brought forth a new, fresh vision of the role of design and ambitiously hinted at what the future might look like. In many cases, they hit the mark. It was indeed a discovery journey, like that of Columbus five centuries earlier, only this time it was America that discovered Columbus, or rather Colombo. In fact, Joe Colombo’s ‘Total Furnishing Unit’ was part of the trip, serving as a tribute to the award- winning designer who had passed away the previous year. Colombo had perfectly understood that the future of urban living would entail smaller housing, and imagined a self contained living space that came complete with a fully fitted kitchen, a bathroom, a sleeping corner and a wardrobe, all in 28 sqm.

Other participants, among the many chosen by Ambasz truly representing Italy’s finest and most disrupting design minds of the time, included Ettore Sotsass, Gae Aulenti, Vico Magistretti, Ugo La Pietra, Gaetano Pesce, Alberto Rosselli, Mario Bellini, Marco Zanuso.

The expedition could also count on renowned design studios such as 9999, Archizoom, Gruppo Strum, Superstudio, further enriching the diverse array of talents showcased.

All together, they embodied the most formidable expression of design genius in the post-1968 era, all loaded into the cargo of the admiral’s ships: the Reformist, the Conformist and the Contestatory. This was in fact the subdivision of the “Objects” section of the exhibition, displayed outdoors, while the ‘Environments’ section’s pieces were exhibited in the interior formal spaces of MoMA. They were themselves classified under three conceptual categories: ‘Design as Postulation’, ‘Design as Commentary’ and ‘Counterdesign as Postulation’.

Such was the significance of the operation, providing a global showcase for Italy, that it had the support of both institutions and corporate Italy, from the Ministry of Foreign Trade and the Italian Institute of Foreign Trade (I.C.E.) to Gruppo ENI, Lanerossi, Fiat, Olivetti, Alitalia and many others.

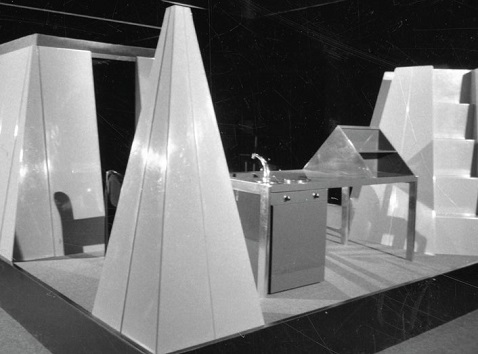

CREDIT: DIGITAL IMAGE, THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK/SCALA, FLORENCEINSTALLATION VIEW OF THE EXHIBITION ‘ITALY: THE NEW DOMESTIC LANDSCAPE’. MOMA, NY, MAY 26, 1972 - SEPTEMBER 11, 1972. GELATIN SILVER PRINT, 1 X 1 1/2’ (2.5 X 3.8 CM). PHOTOGRAPHER: LEONARDO LEGRAND (COPYRIGHT: THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART,NY). THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART EXHIBITION RECORDS, 1004.108. THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ARCHIVES, NEW YORK. OBJECT NUMBER: IN1004.24“

Living Unit: Gae Aulenti's Vibrant Pyramid-Shaped Oasis of Contemporary Domestic Life, commissioned by Kartell. The pyramid was to become a common sight in her work, a sort of hallmark also found in some of her most famous architectural urban projects”

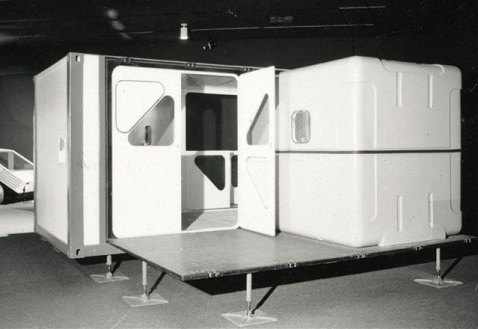

CREDIT: DIGITAL IMAGE, THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK/SCALA, FLORENCEINSTALLATION VIEW OF THE EXHIBITION ‘ITALY: THE NEW DOMESTIC LANDSCAPE’, MOMA, NY, MAY 26 THROUGH SEPTEMBER 11, 1972. CURATORIAL EXHIBITION FILES, XH. #1004.THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ARCHIVES, NEW YORK. PHOTO: LEONARDO LEGRAND (COPYRIGHT MOMA). ACC. N.: IN1004.8

“Mobile Housing Unit”: Zanuso and Sapper’s Revolutionary Concept for Portable Emergency Shelter. It would fit into a 20ft (6.10 mt) ISO container when folded up.

DIGITAL IMAGE, THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK/SCALA, FLORENCEINSTALLATION VIEW OF THE EXHIBITION ‘ITALY: THE NEW DOMESTIC LANDSCAPE’, MOMA, NY, MAY 26 THROUGH SEPTEMBER 11, 1972 CURATORIAL EXHIBITION FILES, EXH.#1004. COPYRIGHT: UNKNOWN. ACC. N.: IN1004.234 (MA325).

Micro Environments: Sottsass’s modular living spaces redefining interior flexibility. The fineglass boxes featured casters and could be moved around the house to create endless configurations and layouts according to inhabitants’ needs.

CREDIT: DIGITAL IMAGE, THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK/SCALA, FLORENCEINSTALLATION VIEW OF THE EXHIBITION ‘ITALY: THE NEW DOMESTIC LANDSCAPE’. MOMA, NY, MAY 26, 1972 THROUGH SEPTEMBER 11, 1972. CURATORIAL EXHIBITION FILES, EXH.#1004. PHOTOGRAPHER: LEONARDO LEGRAND (COPYRIGHT MOMA).

ACC. N.: IN1004.41

"Kar-a-Sutra: Mario Bellini's Futuristic Vision Transforming the car into a Social Hub, anticipating Monospace and MPVs, for Citroën. Notice the lines and the ribbed plastic bodywork, typical of the Méhari, launched in the 60s”Mario Bellini’s astonishing Kar-a-Sutra concept car for Citroën was also part of the this section. His attempt at liberating car interiors from the fixed constraints of the auto industry and make them a place for conviviality paved the way for the design of future monospace and MPV (Multi Purpose Vehicle) models.

The Design as Commentary section featured just one entry: Gaetano Pesce’s post-apocalyptic housing unit envisioned for the year 2000, presented as an archaeological discovery from the 3000s, while the Counterdesign section was a showcase of provocation across various media, from the oral description of a totally empty space by Archizoom, to Ugo LaPietra’s Telematic House, a visionary anticipation of domotics, to the “Supersuperficie” (Supersurface) void of any object by Superstudio and Enzo Mari’s ‘Proposta di Comportamento’ behavioural recommendations. Yet they all had the great merit of forcing a serious reflection on the profound changes taking place in society at the time.

Objects of desire

While much of the work featured at MoMA seemingly expressed criticism of consumerism, paradoxically, many of the exhibited items have since become iconic examples of design and highly sought-after collectibles. This was particularly true among the 180 entries in the Objects section, from Vico Magistretti’s chairs for Artemide, to Zanuso and Sapper’s portable TV set for Brionvega, to Piero Gatti’s ‘Sacco’ sacklike armchair for Zanotta and many others.

Beyond MoMA’s walls, the exhibition won widespread acclaim and support, pushing boundaries and anticipating societal shifts. It also and foremost underscored Italy’s emergence as a global design powerhouse. The provocative designs challenged prevailing norms and prompted critical reflection on societal changes. Many showcased items have since attained iconic status, proof of the enduring impact of Italy’s avant-garde scene. In retrospect, the 1972 exhibition stands as a testament to Italy’s design legacy and its ongoing influence on the global design landscape.

Copyright © Homa 2024

All rights reserved

.jpg?VGhlIFBlcmZlY3QgU2xvdC1pbijmraPnoa4pLmpwZw==)

.jpg?MTkyMHg3MjDvvIhkZXPvvIkuanBn)

.jpg?MTAyNHg3NDDvvIhkZXPvvIkuanBn)