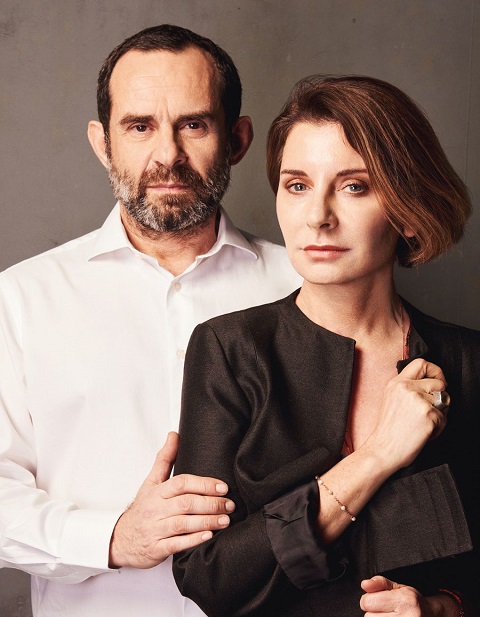

DM interviews Ludovica Serafini and Roberto Palomba, from Palomba & Serafini Associati, the humanist architects and designers who put the users’ wellbeing at the center of their beautiful, inspiring universe.

What stands at the origin of your design vision, and how did it evolve over time?

Ludovica Serafini: The vision and awareness of the whole is the dominant concept that generates all of our projects, details then derive from that prospect. In life, it’s very important to have a path to follow: when you’re working on a project, you need to know exactly what your objectives are. From there your road is quite straightforward, yet it can be extremely winding and full of ambushes and crossroads. You must know exactly where you want to get to. The human being stands at the center of the vision of Studio Palomba & Serafini. There is nothing that we design that doesn’t concern the human being, and it’s wrong to design anything that doesn’t have as an end the wellbeing of the individual. Our core belief is that “good architecture is that which makes the human being using it happy”.Is there an area of design that you prefer above all others? If so, for what reason?

Ludovica Serafini: No, we rely purely on chance to select projects: we let them come to us quite accidentally, so we don’t really get to choose any particular field. We’re like the sea, in the end all rivers come to us, and we just take what comes in.

Ludovica Serafini and Roberto Palomba have talked to DM about their design philosophy and approach to innovation. The story they are telling is that of a profound passion for their work and a clear cut vision about how architecture and design should first serve the wellbeing of the human kind, and start from the conceptualisation of the whole to then concentrate on meaningful, emotional and highly functional details.

What’s the difference between simply “filling” a space and “designing” it according to your conceptual vision?

Ludovica Serafini: None, it’s the same. Space is a void, it’s anonymous, as wonderful as it can be. It doesn’t have a real value until it’s occupied and used by a human being. The value comes when we make that space suited to our needs. Architectural space is like a book, it’s a shell, then you need a pen and you have to write the words in to fill the pages. You need to have some concept, though, for it to make sense. Space is the place that allows you to tell a story: it might become a hotel hall, or a non-place between two wings of a house for you to relax, but regardless of what that space becomes, it will come out of anonymity and start existing. Purpose is fundamental. Sometimes I find it difficult when clients tell me to “just throw in a couple of sofas in that corner”. Easy, right? Not at all! What’s the purpose, who needs to use that space? Where’s the entrance, how high is the ceiling? Is it a passageway? All these are fundamental questions for that space to be meaningful. When a space is well constructed, it’s like eating a piece of a delicious cake: it’s got flour, sugar, egg, milk, maybe vanilla, chocolate chips, yet once it comes out of the oven you can’t separate the individual ingredients, they’ve become a perfect whole. You’ve hit your objective, and you achieved it through planning and design.

“Anything that’s specialised and focussed is destined to fail, sooner or later, for it doesn’t leave space for contamination”- Ludovica Serafini

Is there a project in particular that best incarnates this vision?

Ludovica Serafini: All children are equally loved by their parents. Some time ago we did this charming little guesthouse here in Milan. It was adorable. When the owner, a friend of ours, called to tell me he was selling it, I lost my sleep over it for a month. But yes, there are certain projects I found more interesting than others, like my house in Sogliano. The results exactly matched the objectives I had set myself. There also was Palazzo Daniele, where the collaboration with the owner was marvellous. We managed to do something really interesting, full of innovations, but in a simple manner. Simplicity doesn’t need to be shouted, it expresses itself quietly. This all creates a wealth of experience that can be used in future projects. The boat project, too, I found very interesting, although it remained on paper. We were asked to provide a concept for a yacht. My initial idea was that I wanted a proper house, but one that would lay in the water. I started off with the typical sketch of a house, like the ones children draw, with a pointed roof, windows and everything, and I sat it into the sea. This was the first yacht with a domestic, homey aesthetic. There were large, proper full height windows like the ones in a loft. Yachts traditionally have cabins, with narrow windows, and you lose every perception of the horizon and the outside world. Although it was never built, it set a new trend in the world of nautical design. Initially, we were told that “this design doesn’t belong to the nautical world”. That struck me, and I replied “there isn’t such a thing as a nautical world, there’s only a people’s world who loves the sea”. Anything that’s specialised and focussed is destined to fail, sooner or later, for it doesn’t leave space for contamination.

Are there any projects that didn’t go the way you wanted?

Ludovica Serafini: Yes, certainly. Making mistakes is part of the human condition, otherwise we’d all be gods. Putting a remedy to those errors is what it’s all about: 50% of our creativity is about rectifying mistakes. There’s a word that I really dislike, though: problem. Many things can happen in life, but none of these are a problem, they just happen, instead there are lots of solutions. Of course, if you get the design of a chair wrong, you just throw it away, but when that happens with an entire building, it’s somehow more difficult, so you need a great deal of humility in approaching any project.“By removing the superfluous, you achieve true durability, your creation will never become obsolete”- Ludovica Serafini

By looking at your work and career, the term “moving essentiality” comes to mind. Do you recognise yourself in this description?

Ludovica Serafini: It’s spot on. Our intention is to not-create a style, still we must have beautiful ideas, intelligent and respectful ones. We always try to work with local suppliers and materials. Our hotels are built with local materials, by local craftsmen who know best how to work with them. You must never lose sight of the location, of its purpose and meaning. When you get to the essence, and you can even be playful about it, you don’t need to add anything. By removing the superfluous, you also achieve true durability, your creation will never become obsolete.

In your work, how do you strike the right balance between rationality, in the sense of technology, and emotion, in the sense of perceptions and feelings?

Ludovica Serafini: There is no contradiction in terms, something beautiful can be perfectly functional, and vice versa.Roberto Palomba: I recently got into a discussion with a company who wanted me to work on the claim “design and performance”. I told them that design does indeed include performance. There is this basic misconception about design, whereas people think it only refers to the aesthetic element of an object. Design is not the aesthetic part of a project, design is the project in its entirety, and represents its value as a whole. As you said, it’s a matter of balance, and we must ensure that neither of the two elements predominates at the expense of the other, and this comes with experience.

How do you reconcile product innovation and How would you define innovation?

Ludovica Serafini: Thirty years ago, I was designing a bathroom where I included mirrored walls. At the time Roberto was working on bathroom fixtures. I asked him to design a standalone sink for me. I needed to place it in the middle of the bathroom because I didn’t want to drill holes in the walls. That’s how the first freestanding sink was born. This is innovation, not technological innovation, but typological. By this I mean there are many kinds of innovation.Roberto Palomba: As a studio, we have a certain inclination for typological innovation, this is kind of our hallmark, especially in the bathroom sector. I can say we’ve brought many innovations to this industry, not only in terms of products, but we contributed to evolve the entire market. Not only did we reinvent the wall-hung toilet by removing the side mountings and introducing the concept of a band “embracing” the object, we entirely redefined it by bringing it into the premium end of the market. Also, we broke the paradigm of the classic fixtures suite, whereas the toilet, bidet, sink and bathtub always came in a matching series. We designed individual products to be mixed and matched with other furniture elements, giving much greater freedom in the design of bathrooms. It was a true revolution. This idea of going beyond the single object, or typological innovation, cuts across our whole work, which is characterised by the concept of “meta-projects”, where design impacts and innovates entire sectors.

“Home interior is inviting itself into the kitchen” - Roberto Palomba

Moving on to another domestic space, the kitchen, how did your approach to this subject evolve over the years, especially in relation to the current trends in the field?

Ludovica Serafini: The trend today is to consider the kitchen as the center of the home, so it has become the center of domestic living. Alas it does so while maintaining the typical aesthetics of a kitchen. Why should I live in a kitchen environment? I’d rather have the aesthetics of the rest of the house come into the kitchen, and it’s precisely what we’re doing with one of our latest projects, developed for Elmar: making a kitchen domestic. Of course it keeps all of the technological features that belong to a kitchen, but it is characterised by certain proportions, by materials and furniture that have a strong connection with tradition. It was conceived as a display piece for our client’s showroom, and the underlying theme we worked on is that of the metropolitan kitchen. Quite often, displays in showrooms have inflated proportions that don’t correspond to the real spaces in actual houses. In this case we wanted to give a precise idea of what the kitchen truly would look like in a real home, and precisely in a city apartment. Still, the showroom is impressive and the kitchens on display are stunning while keeping real- life proportions, so details become very important. The message we are conveying here is that the home interior is inviting itself into the kitchen, which starts acquiring many characterising elements you would find in the rest of the home but which it normally lacks.Roberto Palomba: I’d like to add that not enough is being done in that sense at university. While designers and architects receive impeccable formal training, they lack the capacity to see things from different perspectives. Worse, they seem to mistake innovation for “making it weird”. Professors, and even journalists encourage this attitude and tend to reward surprising and odd designs. As a lecturer I always tried to explain students that the real challenge was having the courage to look at things from a different perspective, to view the old with a fresh eye. It is important for new generation designers to understand this, otherwise there is a risk of stagnation, which will then require a revolution in order for this profession to survive. However, I prefer evolution to revolution, and changing our perspective is a good way to evolve.

“Food is culture, and our relationship with the kitchen derives from our culinary cultural background” - Roberto Palomba

In your ideal, educated kitchen, should appliances be visible or hidden?

It depends on whether we designed them!Roberto Palomba: After recently starting to cook, I’ve come to realise that certain appliances can evoke affection, and even have a decorative value. Some of them have become iconic, almost erotic objects, and are put on display in trendy kitchens.

Ludovica Serafini: Appliances are central elements in a kitchen from many points of view, starting with that of the architects, but also of the users and their guests. They need to be easy and intuitive to use while being technologically advanced and complex. However, some of them consume far too much energy. Also, it’s terribly confusing and complicated to find the right aesthetic to match that of your kitchen. If I were to design new appliances, I would want them to be customisable in terms of finishings, handles, materials, colours. This would be very interesting as it would open up numerous possibilities. Also, ease-of-use would be a priority, with them being totally intuitive.

What is you personal relationship with the kitchen, and cooking?

Roberto Palomba: I try and stay clear, since I’m always on a diet, yet recently I’ve started baking cakes which I then give away to friends. One of them recently moved to China, and he keeps posting photos of food on his social media. The relationship we have with food is changing. In one of the projects we did for a hotel, we had the public almost literally walking through their kitchen, with food and its preparation becoming a true entertainment piece. Also, food is culture, and our relationship with the kitchen derives from our cultural culinary background. The kitchen should be a cultivated space within the house, maybe with a library, a place where you can travel in your mind whilst preparing educated food.Ludovica Serafini: I personally hate routines, anything that’s repetitive and boring and that distracts me from my passion, architecture. In fact I never cook, I spend very little time in the kitchen, but I entertain a lot. I like having friends around, and we often prepare something simple on the spot. My true relationship with the kitchen is in Salento (one of Italy’s most Southern regions and notoriously rich of culinary traditions, Ed.): to start with, when I’m there it means I’m not working, so the kitchen becomes the place for creativity, it’s my own kind of yoga. Then it’s positioned in such a peculiar way inside the house that when you start cooking you’ll never find yourself alone, everybody comes along, so it becomes a hub for conviviality. We start discussing about the recipe being made, exchanging opinions, arguing at times. I like it, but it’s not something I want to engage in every day.

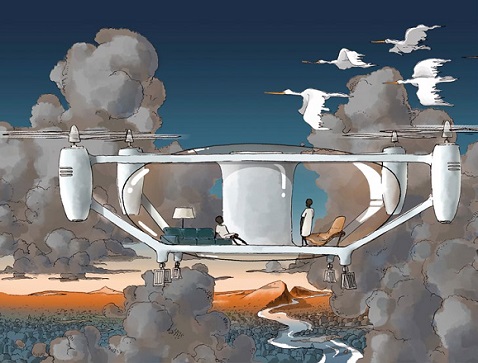

Could you tell us about your most futuristic and forward-thinking project, the drone-house?

Ludovica Serafini: The idea of the drone-house originated from a series of reflections we made around the success of food delivery services. Architects are visionaries, and we started reasoning on what was really essential in a house for us to live in. Younger generations would tend to occupy the sofas, tending to their laptops, so no real need for tables or desks, and by that count chairs become superfluous, too. Sofas are comfortable, and one can sleep on them, so there goes the bedroom! Kitchen? Who needs a kitchen when you can have food conveniently delivered to you doorstep? In the end, if you go on drastically eliminating all the unnecessary parts, you’re left with the bare essentials, i.e. the sofa, and a bathroom. All this is actually very light, so much so we might imagine it being flown around by a drone. You already have drones which can transport people, so why not a drone-house? You’d be able to stop over wherever you’d feel inspired, and send for food and supplies, in a sort of nomadic yet connected lifestyle. As a result, cities as we know them would cease to exist, disappearing altogether.How do these extreme visionary concepts reflect in your current work?

Roberto Palomba: This meta-vision about the future introduces some extreme concepts which we have translated, through a different point of view, into a more traditional approach in some of our recent projects. Take, for instance, the walk- in closet in our house in Milan. Where do people normally have it? Right next to the bedroom, but purely out of convention. You see, the sense of comfort given by common habits and practices often makes you lose common sense. It makes much more sense to place it next to the main entrance. When we come in, we can take off our coats and change into our home clothes, and vice versa. This is only a small example, and the rest of the house is full of these ideas that originate from a deep examination of the real use one makes of a house and of its spaces.You talked about bringing the domestic space into the kitchen. What about taking the kitchen out in the open air?

Roberto Palomba: We architects are great colonisers of space, and we certainly like to expand our work outside the home. Outdoor living started to become fashionable ever since textile producers started offering quality outdoor fabrics. The concept of outdoor changed radically in its perception, and so did the furniture. The same goes for the outdoor kitchen. Outdoor cooking is everybody’s dream, you can unleash your creativity and attempt to cook stuff you’d never do indoors. The outdoor kitchen opens up an entire new perspective on food culture, which is very interesting.

“The sense of comfort given by conventions often makes you lose common sense” -Roberto Palomba

BIO

Ludovica Serafini and Roberto Palomba, the visionary minds behind Studio Palomba & Serafini, have a shared passion for blending outstanding functionality and moving aesthetics, having the human being, the ultimate user of their creations, as the center of gravity of all their work. In their 30 years career, their internationally acclaimed and visionary projects have spun architecture, interior design, and product design.Born and raised in Italy, Ludovica Serafini and Roberto Palomba both studied architecture at the University of Rome. After earning their degrees, they embarked on separate professional journeys before establishing Studio Palomba & Serafini in Milan in 1994.

Drawing from their profound knowledge of design culture and history, they set out to redefine contemporary design. Their collaborative approach, marked by a deep appreciation for craftsmanship and attention to detail, combines a contemporary vision of society’s lifestyles with users’ needs and aspirations, resulting in a diverse portfolio of projects that captivate and inspire.

With a commitment to creating spaces that resonate with emotion and essential authenticity, with a particular sensitivity towards function and the longevity of their products, Ludovica Serafini and Roberto Palomba continue to influence the world of design through their personal approach to innovation.

Copyright © Homa 2024

All

rights reserved

.jpg?VGhlIFBlcmZlY3QgU2xvdC1pbijmraPnoa4pLmpwZw==)

.jpg?MTkyMHg3MjDvvIhkZXPvvIkuanBn)

.jpg?MTAyNHg3NDDvvIhkZXPvvIkuanBn)