DM traced some of the most significant milestones in the technological and design evolution that led to the creation of some small kitchen appliances that became indispensable in the ritual of breakfast, but not only.

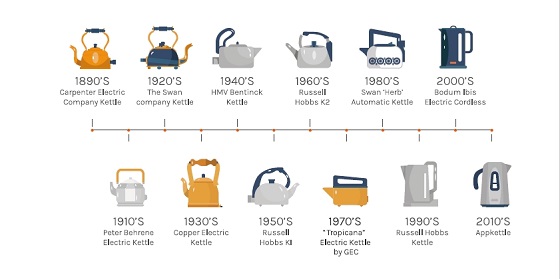

THE KETTLE

The kettle is traditionally understood as a container dedicated to heating tea only from the mid-1700s, when the British East India Company began to trade directly with China, focusing on tea imports. Tea became more widely available and therefore more popular and affordable for all social classes. This also fostered the emergence of a kettle specifically dedicated to this beverage: it was made of copper, a durable, ductile, and excellent heat conducting material. It quickly became common sight in the homes of wealthier British families. In most working-class families, kettles were made of cast iron or enamel.

The first attempts at creating an electric kettle began in the early 1890s. In 1891, American company Carpenter Electric launched its first electric kettle. Two years later, it was the turn of English Crompton & Co. Both kettles had a heating element placed in a separate compartment and took more than ten minutes to boil water. The problem was solved in 1922 by Arthur Leslie Large, an engineer from Birmingham, in the United Kingdom, who worked for Bulpitt & Sons. He invented a kettle containing a submersible electric heating element. It was marketed under the Swan brand. The invention of the whistling kettle is commonly attributed to Londoner Harry Bramson, who sold the patent in 1923. This type of kettle has a device that whistles once the water inside reaches boiling point.

The steam pushing through the device creates a vibration, which then produces a sound.

In 1955, William Russell and Peter Hobbs, founders of British small appliance company Russell Hobbs, launched the K1, the first fully automatic electric kettle. Thanks to the use of a thermostat, it would automatically switch off the kettle once the water reached boiling point. This product marked the evolution of the product also in terms of design as it replaced iron and brass with stainless steel.

A few years later, in 1960, they updated the design and introduced the K2 model: the technology was the same but boasted a sleek, more elegant design, and was finished in polished chrome. Since then, Russell Hobbs has continued to innovate, creating the first cordless kettle, the first 360-degree swivel base, and rapid boiling. In 1992, BODUM, a Danish company, introduced the cordless electric kettle Ibis to the market. Modern kettles are made with a thermoplastic casing and thermoplastic handles. The transition from metal to plastic provided several advantages: besides reducing development costs, they are lighter, more airtight, see-though to check water level, and better insulated.

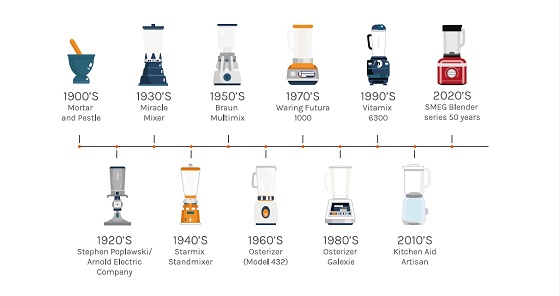

THE BLENDER

Before his creation, mincing and chopping were done by hand only, with a mortar and pestle. In the 1930s, Louis Hamilton, Chester Beach, and Frederick Jacob Osius produced Poplawski’s invention under the Hamilton Beach Company brand. Fred Osius was an inventor and improved the appliance, creating another type of blender. He approached Fred Waring, a popular musician but also a dreamer with an engineering degree, who funded and promoted the “Miracle Mixer,” released in 1933. However, the appliance had some issues with the seal of the jar and the blade shaft, so Fred Waring redesigned the appliance, and in 1937, he launched his blender, the Waring Blendor, which became widely used in public venues, bars, and restaurants. It became popular in households as well, thanks to the advent of television, where a 30-minute commercial dedicated to the blender aired in 1949. By 1954, it had sold one million units.

In 1937, William Grover Barnard, founder of Vitamix, introduced a product called “The Blender,” a reinforced blender with a stainless steel container replacing the Pyrex glass jar used by Waring.

In 1946, John Oster, owner of barber supplies company John Oster Manufacturing, acquired Stevens Electric and designed his own blender, marketed under the Osterizer brand. It was the first blender suitable for everyday use for the preparation of meals.

In Europe, the popularity of household appliances grew significantly between 1930 and 1970, especially in Northern Europe where brands like AEG, Electrolux, Siemens, Braun, and Philips were well established, and to a considerable extent also in England and France.

In 1943, Swiss entrepreneur Traugott Oertli launched the Turmix Standmixer blender, revisiting Waring’s design.

After WWII, several companies offered different models of blenders. The first to do so was German company Electrostar, with its Starmix Standmixer (1948). The product had numerous accessories (coffee grinder, cake mixer, ice cream maker, food processor, thermos jug, milk centrifuge, juicer, and meat grinder). In 1950, Max Braun launched the Braun Multimix, featuring a glass bowl for making batter bread and a juicer, similar to the one developed by Turmix.

THE TOASTER

However, it was with the Toastmaster 1A1, invented in 1926 by Charles Strite, that this small household appliance achieved worldwide success. The device was accompanied by the slogan “You don’t have to watch it, the toast doesn’t burn”. Unlike competitors’ models, it was equipped with an adjustable timer and a spring mechanism that ensured the toast would be automatically ejected when time was up.

Although it wasn’t cheap, Toastmaster was a global success right from its launch. About 1.2 million units were sold each year throughout the 1930s.

However, what boosted its popularity and made it a familiar sight in every household was the commercial sale of pre-sliced bread: it began in 1928 with the Chillicothe Baking Company of Chillicothe, Missouri, selling “Kleen Maid Sliced Bread,” and was further popularised by Wonder Bread.

In terms of design, the early toasters imitated small items of furniture. In the 1930s, they replicated the Art Deco style of buildings, while in the 1940s and 1950s, their aesthetics evoked the streamlining of the automotive industry. The evolution of its design progressed hand in hand with technology advancements. In 1947, Kenneth Wood invented the electric toaster that did both sides of your toast at a time, and a few years later, some models were capable of calculating the exact toasting time. By the 1960s, toasters were in every household and had become a commodity. From the 1970s, they started featuring wider slots, and had the ability to toast up to six slices of bread, while using heat-resistant plastics for the casing. Millennial toasters have microchips assisting in various sophisticated functionalities, including defrosting and warming croissants, bagels, and muffins.The latest models are constructed entirely from bioplastics, reflecting a commitment to environmental consciousness.

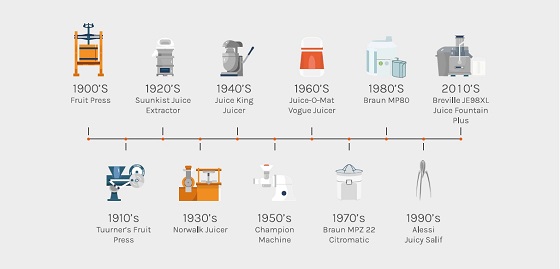

THE JUICER

The history of electric juicers traces back to the early, simple manual models, typically crafted from wood. Between the 19th and 20th Centuries, there was a boom of patents for their mechanisation. The mechanical principles varied, but essentially they all described systems that applied direct pressure on the lemon, or orange, without rotation. They differed only in the means used to achieve this effect, which most often involved levers or pressure of some kind.

Among the pioneers of the modern juicer, Joseph L. Fuchs, an American of German origin, who applied for a patent as early as 1925, and Norman Walker, a British businessman, scholar of nutritional health, and an advocate of the vegetarian movement. Based on his studies, conducted in the 1930s, Walker invented the Norwalk Juicer, still on the market today. The machine was large but effective: it first grated and squeezed fruits and vegetables, then pressed the pulp in a linen bag using a hydraulic press.

In the mid-1950s, the first “masticating” juicer was invented, yet the high speed of the rotating shaft was excessive and caused friction, heating, and the destruction of live enzymes and other nutrients. Since then, it has undergone many design improvements and is probably the most widespread and successful model today. The universal adoption of juicers occurred in the 1960s thanks to the production of more efficient devices in terms of juice extraction, with less physical effort. In the 1990s, designers shifted to double-gear systems, eliminating overheating and preserving nutrient-rich juices.

Among the most iconic products in terms of design, the Braun MPZ 22 electric juicer, better known as Citromatic, designed by Jürgen Greubel and Dieter Rams in 1972, deserves to be mentioned. This device embodied the second of the ten principles of good design as postulated by Rams: it says “A product is bought to be used. It must satisfy not only functional but also psychological and aesthetic criteria. Good design emphasises the usefulness of a product while disregarding anything that could detract from its functionality.” For decades, Citromatic has been one of the most ubiquitous products in kitchens, and its original design was eventually and only slightly modified by Braun after more than twenty years. The most iconic juicer of all time, and also the one that sparked most discussions, is undoubtedly the Juicy Salif, designed by Philippe Starck for Alessi. Made of die-cast aluminum with a polished effect, it features curvy forms composed of a central body from which three long legs extend. Since its launch in 1990, it has become part of the collections of nearly twenty museums worldwide, including NYC’s MoMA and Centre Pompidou in Paris. Not to mention its featuring in various films, TV series, and numerous book covers. Born out of Starck’s imagination while squeezing a lemon on a dish of calamari during a vacation in Capraia, in the Tuscan archipelago, it is indeed one of the objects that garnered the most attention worldwide. According to the designer himself, its primary function was to generate curiosity and stimulate conversations.

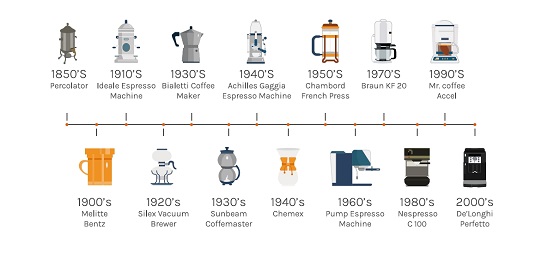

COFFEE MAKER

The preparation of coffee is a centuries-old affair, starting with the use of infusion and brewing techniques. Coffee grounds were submerged in hot water or boiled to extract the aroma for a cup of coffee. But it was only in 1884 that the first espresso machine came about, transforming the processes of home and commercial preparation of coffee with new specialties like espresso or cappuccino.

Before 1865, coffee was obtained using the coffee percolator. That year, American James Mason filed the first patent for a machine that, placed on the stove, allowed the coffee to be infused “by gravity”, continuously passing boiling water through the ground beans until the desired intensity was reached. However, it had the defect of producing beverages with a bitter taste.

1884

Angelo Moriondo invents the first espresso coffee machine. His invention was patented and used for the first time at the General Exhibition in Turin. The machine was not marketed; Moriondo handcrafted only a few units and used them in his commercial establishments.

Luigi Bezzera patented a commercial version of the espresso coffee machine in 1901, and later sold the patent to Desiderio Pavoni, who, began mass production.

1908

In Germany, Melitta Bentz invents the first drip coffeemaker using a paper filter for brewing. This coffeemaker revolutionised the way coffee was prepared by eliminating manual labour and automating the brewing process using a filter basket filled with ground coffee and hot water pumped from a water tank.

1929

Italian designer Attilio Calimani patents a more advanced version of the plunger coffee maker. This filtration system, better known as the French press, was patented in France in 1852 by Meyer and Delforge. This initial version consisted of a cylindrical container and a plunger attached to the lid equipped with a perforated tin filter and flannel discs. The “Italian” version was further perfected by Bruno Cassol and Melior. The French press allowed for both hot and cold extraction.

1933

Birth of the moka pot, patented by Alfonso Bialetti along with Italian inventor Luigi de Ponti. The Italian entrepreneur wanted to create a lightweight and inexpensive coffee machine. He was inspired by observing some women doing laundry with the “lisciveuse”.

1948

Achille Gaggia introduces the lever espresso machine based on the use of water instead of steam.

1961

Italian company Faema takes a further step forward by launching its own pump-driven espresso machine, powered by a motorised pump instead of physical force. The design of this machine has become the standard for coffee production worldwide.

1986

Swiss company Nespresso revolutionises the market with the single-serve coffee machine. The first model (C-100) was reminiscent of the shapes of espresso machines used in bars, while initially there were only five blends available.

2000

The use of electronics makes espresso machines increasingly sophisticated and intuitive. Technology advances affect all the main elements characterising a coffee machine: from the design of the machines to the level of automation, from function control to energy-saving performance.

Current automatic models are able to independently manage the entire coffee preparation process: from grinding the beans to making various coffee-based drinks, preparing all milk-based drinks, and providing hot water for steeping tea and infusions.

All the images in this article are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License - www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 credits: https://www.homeadvisor.com/r/evolution-of-kitchen-appliances/

Copyright © Homa 2024

All rights reserved

.jpg?VGhlIFBlcmZlY3QgU2xvdC1pbijmraPnoa4pLmpwZw==)

.jpg?MTkyMHg3MjDvvIhkZXPvvIkuanBn)

.jpg?MTAyNHg3NDDvvIhkZXPvvIkuanBn)